THE PUBLIC FESTIVAL

A DIACHRONIC GLIMPSE AT ITS SOCIO-ECONOMIC & POLITICAL ROLE

A conference which in its invitation states that “It is about a very old social institution whose original meaning in its Greek context (Panegyri) was people's general assembly.”

Paper Submitted by Slobodan Dan Paich, Artship Foundation.

The author of this paper starts from a premise that within public assemblies and gatherings, in the territories under influences of classical Greek civilization, processions, blessings, rituals, performances and dance took place. This paper explores dances of healing and release traditionally danced by women.

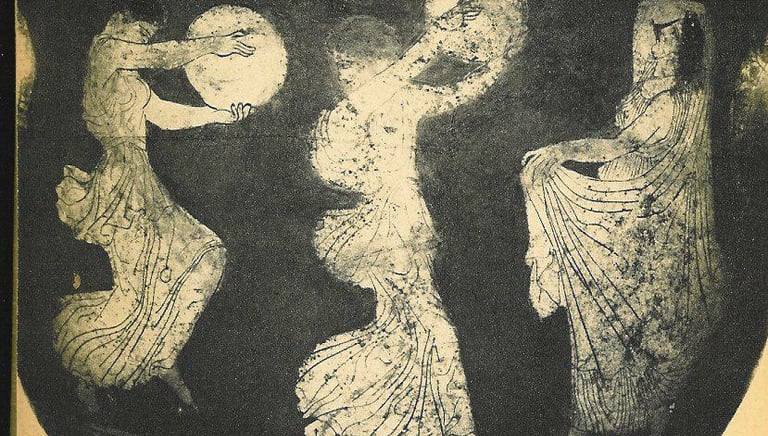

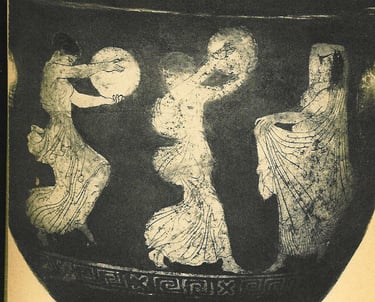

Bacchantes Dancing to a Tympanon, Detail of a red figure on a black background. About 450 B.C.E. (Paris, Louvre)

MAGNA GRAECIA/TARANTELLA

Abstract

We present an overview of the literature, with a series of tentative hypotheses and open questions, about possible relationships between the southern Italian dance Tarantella, particularly the Pizzica type, and the Dionysian festivals and Pan worship of Magna Graecia and the Greater Mediterranean region. We conclude with discussions of the social and psychological functions of festivals, in the context of the ideas of “just excess” and “recovered closeness”, as articulated by Professor Philippe Borgeaud in his book “The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece” (The University of Chicago Press, 1988).

Origins of Our Work on Public Celebrations and Festivals

ARTSHIP Foundation was established as a cultural arts and public benefit foundation in the San Francisco Bay Area of California in 1992. We are dedicated to the study, understanding and creation of the “Community Commons.” We intentionally advocate for and demonstrate that art-making and cultural activities are strong convening forces for creating and re-interpreting reasons and opportunities for public gatherings in local communities. Our work also addresses the need to value and protect the rights of people globally to gather and celebrate in public places in a community setting.

To enlarge our understanding of the value of public celebrations, we study the ancient festivals, celebratory practices, folklore, myths and ceremonies of many cultures. Our objective is to gain cultural sensitivity, appreciation of diversity, and respond to the tensions amplified by the uprootedness in American life. These include the social implications of being in more than one culture at the same time, and being a child or grandchild of an immigrant or refugee. Our studies are always background research for creation of new and multi-disciplinary work in the arts and culture-making.

The Tarantella dance has a unique position in the history and practice of folkloric dance in Europe. It is among the few known dances with healing elements, believed to be an antidote to the tarantula spider’s bite. It also is the conscious restorer of psychological balance, as well as a social and courting dance.

Starting Point: Dionysian Worship

The starting point of this paper is to focus on some aspects of the “Panegyri” and to narrow the focus to a discussion of assemblies and gatherings, where specific dances by women played an essential role. Thus, we come to the festivals and celebrations of Dionysius.

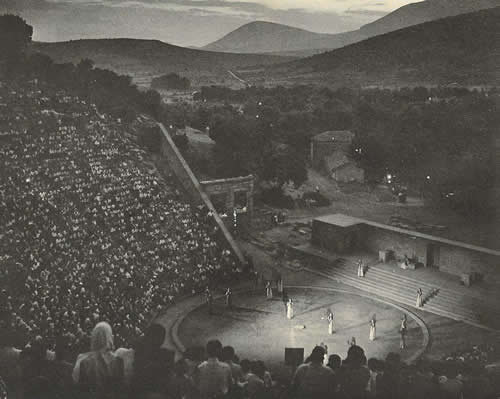

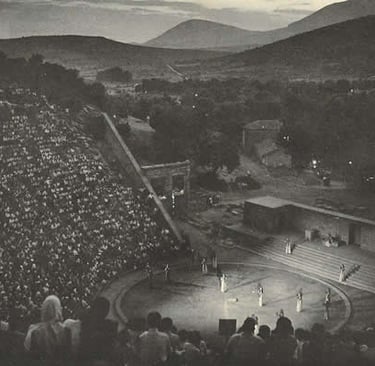

Performance of Euripides’ Hippolytos, August 1954, in the Theater at Epidaurus, from the History of the Greek and Roman Theater by Margarete Bieber

To set the stage and create a referential context, we recapitulate accepted and well-known facts about aspects of Dionysian rites and lore. This background is based primarily on the encyclopedic entries in Oskar Seyffet, “Dictionary of Classical Antiquities,” revised, edited and enhanced by Henry Nettleship and J.E. Sandys, and on L. F. Miler (translated from the French into Serbian) “Pojam Duse kod Grka – dionisov Kult,” in addition to notes from author’s student days.

Dionysian rites and lore

It is to the worship of Dionysus that the “dithyramb” and “drama” owe their origin and development. The dithyramb is a chorus of approximately 50 men and boys assembled to honor Dionysus. It is conjectured that, over time, one member of the chorus began to sing separately from the rest, marking the beginning of the emergence of “drama” in early Hellenic culture.

The deity Dionysus is closely related to other gods — Demeter, Aphrodite, Eros, the Graces and the Muses, and also to Apollo. It is commonly accepted that the grave of Dionysus was at Delphi in the innermost shrine of the temple of Apollo.

Secret offerings were brought to the grave of Dionysus at Delphi. In every second or third year (historians differ on this), and after spending an interval in the lower world, Dionysus is born anew. Women who were celebrating the feast invoked the newborn god. During their celebrations, they dressed in animal skins and carried poles called “thyrsi” which were entwined with ivy and topped with pinecones. The most ancient representation of Dionysus consists of wooden images with the phallus as the primary symbol of generative power.

In Attica Dionysus was worshipped at the Eleusinian mysteries with Persephone and Demeter, under the name of Iacchos, as brother or bridegroom of Persephone. At Delphi, Dionysian festivals proceeded from the innermost sanctuary of Apollo to the neighboring mountain of Parnassus. Festivals celebrating the extinction and resurrection of the deity, were held by women and girls only, amid the mountain at night, every third year, around the time of the shortest day of the year. The rites, intended to express the excess of grief and joy at the death and reappearance of the god, were wild. The women who performed them were hence known by the expressive names of Bacchae, Maenads, and Thyiades. They wandered through woods and mountains, their flying locks crowned with ivy or snakes, brandishing wands and torches, accompanied by the sounds of drums and the notes of the flute, with “wild” dances, and “insane” cries of jubilation according to most historians.

As a god of the earth Dionysus belongs, like Persephone, to the world below as well as to the world above. The death of vegetation in the winter was represented as the flight of the god into hiding from the sentence of his enemies, but he returns again from obscurity, or rises from the dead, to new life and activity.

In Italy the indigenous god Liber, with a feminine Libera at his side, corresponded to the Greek god of wine. Just as the Italian Ceres was identified with Demeter, so these two Roman deities were identified with Dionysus, or Iacchos, and Persephone, with whom they were worshipped under their native names, but with Greek rites, in the temple on the Aventine. Liber or Bacchus, like Dionysus, had both a country festival and an urban festival. The country festivals were held, with unrestrained merriment, at the time of grape gathering and straining of the wine. The urban festival, held in Rome on the 17th of March, was called Liberalia. Old women, crowned with ivy, sold cheap cakes (libra) of flour, honey and oil, and burned them on little pans for the purchasers. The boys took their toga virilis or toga libera on this day, and offered sacrifices on the Capitol. Side by side with this public celebration, a secret worship, the Bacchanalia, found its way to Rome and into the rest of Italy.

Sacred Dances

From the chapter titled “Ecstatic Dances,” in the book by W.O.E. Oesterley, “Sacred Dances in the Ancient World,” (Dover Publications, 2002 reprint of 1923 edition), we read:

“Therefore we naturally think of the mythic Maenads, and more especially of their historical counterpart, the Thyiads, who are much the same as the feminine Bacchates. According to the myth concerning the origin of the Thyides, they were so called because the first priestess of Dionysos was named Thyia, and she performed orgiastic dance in his honor; hence all women who danced, or “went mad,” in honor of Dionysos were called Thyiads after her. The Maenads are depicted on many Greek vases and bas-reliefs, so that we can form a good idea of the kind of dances they were supposed to perform; and these were, of course, the actual form of the dances executed by the Thyids.”

W.O.E. Oesterly’s statements are important here, both for their description and naming of the festival dancers, and for making the distinction between mythological Maenads and real women. This raises important questions for this paper:

For the women involved, which elements were traditional and prescribed by ritual?

Which were individual and expressive of experience?

And what is relationship between the two?

W.O.E. Oesterly continues:

“ … they all exhibit one or another phase of orgiastic dance, the same mad revelry, the utter exhaustion and prostrate sleep; and they represent the kind of dancing which historically was performed by the Thyiads.”

“ Mad One, Distraught One, Pure One, are simply ways of describing a woman under the influence of a god, of Dionysos.”

Those who took part in these dances are described as ‘raving and possessed’;their over-wrought state caused them to see visions; the god was believed to be present, though invisible; and at the Dionysos festivals the maidens celebrated his presence, thus direct contact with him by his worshippers was effected.

The following excerpt is one of the cornerstones of this inquiry. Here the author of this paper (2005) continues to quote W.O.E. Oesterly (1923) who cites Pausanias (2nd century A.D.), who was puzzled by Homer (~ca. 850 B.C.):

“ In an interesting passage in Pausanias we read: ‘But I could not understand why he (i.e. Homer. In Od. XI. 581) spoke of the fair dancing grounds of Panopeus till it was explained to me by the women whom the Athenians call Thyiades. The Thyads are Attic women who go every other year with Delphian women to Parnassos, and there hold orgies in honor of Dionysos. It is custom of these Thyiads to dance at various places on the road from Athens, and one of these places is Panopeus.’ ”

We also refer to Pausanias, V.XVI.5, where we read of the “Sixteen Women” who form two choruses, one of Physcoa and the other of Hippodamia. According to Pausanias the two names represent women who were early and significant celebrants of Dionysus.

Might they also represent choreographic remainders for the festival procedures, or types of celebration, something like tragoi in tragodia?

From Pausanias we sense that the celebrants already knew the dance steps and performed them. The women of Attica and women of Delphi knew the same dance.

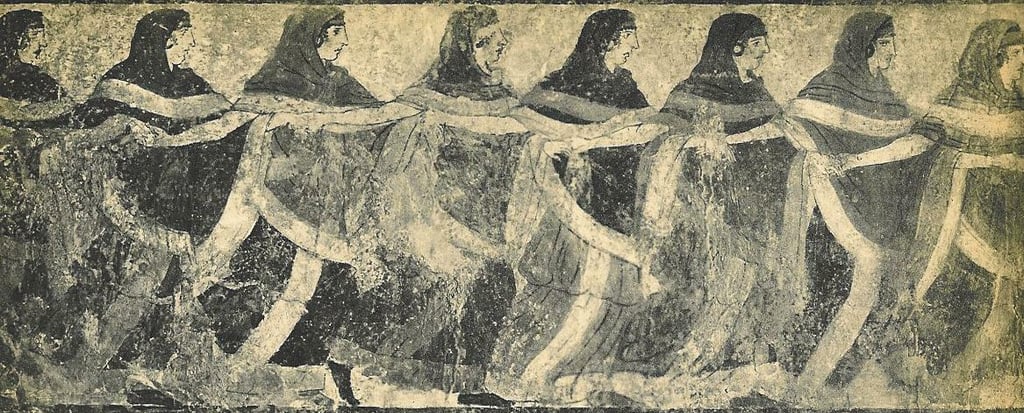

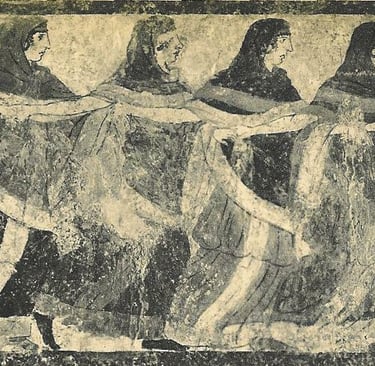

From the illustration below, we can see the Greek “khoreia,” choral dancing to music, very clearly in the 400 B.C. fresco, on the chorus painted on a Greek tomb from the Ruvo di Pulia region. The dance, illustrated in the fresco, still is practiced to this day in Megara, and is called “Tratta” in southern Italy. The women of the chorus are united in four sections of nine each, with each section led by a dancer or a musician. They hold each other by the hand, two by two, and form a sort of chain, with crossed links, which progresses in a solemn, side-wise step, in a series of five steps forward and three steps back.

Performance of Euripides’ Hippolytos, August 1954, in the Theater at Epidaurus, from the History of the Greek and Roman Theater by Margarete Bieber

Chain Dance. Detail of a fresco on a Greek tomb, about 400 B.C.E., Ruvo di Pulia, southern Italy. discovered in 1833 and preserved at the Museo Nationale, Naples.

Is this possibly a partial expression of the lamentation dances for the death of Dionysus?

Might it also represent the “just excesses,” the excess of grief prior to an excess of joy at the god’s rebirth?

W.O.E. Oesterly continues by quoting a native of Magna Graecia, Diodorus (1st century B.C.):

“…In many towns of Greece every alternate year Bacchanalian assemblies of women gather together, and it is custom for maidens to carry the thyrsus and to revel together, honoring and glorifying the god; and for the (married) women to worship the god in organized bands, and to revel in every way to celebrate the presence of Dionysos, imitating thereby the Maenads who from of old, it is said, constantly attend the god.”

From the material referenced thus far, one may conclude that women played a critical part in the festivals of Dionysus. We also see that at one stage the dance is choreographed by ritual or tradition, and at another stage their gathering becomes an ecstatic celebratory dance.

Description of Key Source Elements

In following strong or tentative connections to and from Tarantella dances, our research came upon striking, beautiful and provocative fragments. Some of them open more questions than give answers. All of them lead to some form of festival, celebration, gathering or assembly in the territories under strong influence of ancient Hellenic culture. In the following material we enumerate, exhibit, comment and ask some questions centered around some key elements and fragments.

Fragment 1. Sleeping Bacchanite. At the Museo Nacionale in Naples there is a fresco showing a dancer, a Bacchanite, asleep while another dancer wide awake is watching over her. A tambourine with its rhythm-expressing rings and a staff or wand (thyrsi) crowned with a pine cone for Dionysus worship are beside her.

This image of the watchful companion, and some other fragments from cultural history, discussed later, open the questions:

Was there an organized interplay of structure and spontaneity of some of the ritual dances?

What does this procedural interplay of structure and expressiveness offer to a festival participant?

Was there an observance helping festival celebrants to express to the point of excess and for a while act and behave outside of social norms?

And did this observance also provide a safe environment for a healing dance assembly?

Fragment 2. Pan Worship. P. Borgeaud, in his book “The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece,” says:

“The isolated haunts of Pan, a territory devoted to the hunt and to the rearing of goats and sheep, are in principle closed to women. Pseudo-Heracleitus has it exactly right: this is a sphere of frustration. This landscape has been set aside for strictly masculine projects – except that the maenads sacred to Dionysus can enter it, along with the nymphs of Artemis. The ritual practices of these creatures, midway between myth and social actuality, are marked by a steady opposition to normal feminine behavior. The maenads, like nymphs, flourish outside of social space. The nymphs have nothing at all to do with the city, while Dionysus’s female companions, who are often wives and mothers, cut themselves off for a time from the cultural order to which they normally belong: Dionysiac frenzy tears them for a time from the city, toward the wilderness, far from men.”

Further questions emerge from this reading:

What do you do if you are a maiden, matron, widow or a crone, living in a small community where mythological regeneration cannot happen in mountains and distant caves?

Could you turn to a practice, event, or formal or informal “institution” in your community for reprieve and outlet?

Did such institutions and practices exist at that time?

Wall painting of the Sleeping Bachanite: Baccanate Addormentata, 6th century A.D., Pompeian, Greco-Roman fresco preserved at the Museo Nacionale Di Napoli.

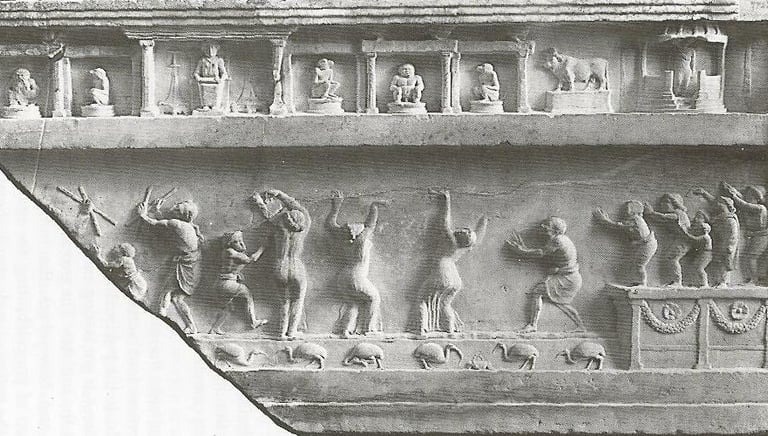

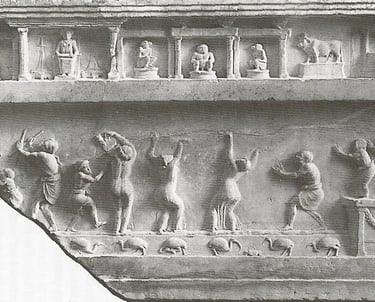

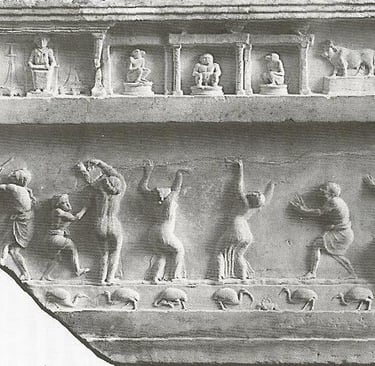

Relief from Aricia, now in the Museo delle Terme, Rome and published in “Cults of the Roman Empire,” by Robert Turcan. [Blackwell Publishers Inc.,1996, p. 19]

Fragment 3. Maenade Dance. In a relief from Aricia, now in the Museo delle Terme in Rome, we see a potential representation of an expressive women’s dance as a part of an assembly, perhaps in the context of a Dyonisian-Isis worship ceremony. For the scope of this paper we do not enter the intriguing and complex iconography with its Egyptian and Hellenistic elements. We include this fragment here to be a strong illustration of the presence of the “maenade type” of dance in organized gatherings of the Greco-Roman world.

Fragment 4. Elements of Women’s Festivals. In the book “Women’s Religions in the Greco-Roman World: A Sourcebook,”edited by Ross Shepard Kraemer, (Oxford University Press, 2004 p. 22), there is an entry from the 3rd century B.C.E.:

“Ritual Equipment for a Women’s Festival in Hellenistic Egypt“

“Demophon to Ptolomaeus, greetings. Send us at your earliest opportunity the flautist Petoun with the Phrygian flutes, plus the other flutes. If it’s necessary to pay him, do so, and we will reimburse you. Also send us the eunuch Zenobius with a drum, and castanets. The women need them for their festival. Be sure he is wearing his most elegant clothing. Get the special goat from Aristion and send it to us …Send us also as many cheeses as you can, a new jug, and vegetables of all kind, and fish if you have it. Your health! Throw in some policemen at the same time to accompany the boat.”

This fragment so vividly brings together the many elements of a women’s festival that we wish the record had revealed more detailed descriptions of procedures, roles and feelings.

Fragment 5. Sapphic Verse. In a similar vein, from her beautiful poem “Dancers,” Sappho presumes that we know what is going on, so she gives us an image of aromas of lawn underfoot knowing that the experiences of her contemporaries will fill in the rest:

In old days Cretan women danced in perfect rhythm around a love altar, crushing the soft flowering grass.” Sappho, Dancers (154, Insert 16).

Fragment 6. Minoan Sculpture of Women’s Round Dance

Rondo of Women Around a Lyre Player, polychrome terracotta of the Middle Minoan III, about 1600 B.C.E., Candia Archeological Museum, Crete, Greece

This sculpture tantalizingly confirms the existence of women ’s dances and, as the proceeding fragment suggests, it raises more questions:

What happened among them?

How did they move?

What was the focus of their gathering

These are questions we may never be able to answer.

Fragment 7. Egyptian Zar. The following fragment of the Egyptian ritual dance Zar may, indirectly, evoke the same sense of women’s trance dances in ancient times, within communities, and in familiar surroundings under special conditions of a festival or religious assembly. Some issues of Zar practices are outside the scope and expertise of this paper, but later on we touch upon their striking similarities to the Tarantella Pizzica and, perhaps in an indirect way to the Pan and Dionysian worship.

Karol Harding in her article “The Zar Revisited” for Crescent Moon magazine (July-Aug. 1996 p.9-10) says:

“The Zar ritual is cathartic experience which functions for women in these cultures as effectively as does psychotherapy in western culture. It involves several aspects which all contribute to its success as therapy:

The patient is the center of attention, and receives the help and concern of her friends and relatives. Her experience and feelings are recognized as valid. As Dance Therapist Claire Schmais explains, ‘it is community based, followers and members are not sent away to be cured…. It creates sense of community while it heals, embracing the individual within a community.’

Rituals are used to create the setting. They have specific players and roles: a leader, a drum corps, a ‘patient’ and participants. These rituals include an altar, the smell of incense, and costumes. Songs are chanted and drums play trance-like rhythms. The zar provides a multi-sensory experience with sights, sounds and smells.

The ritual sharing of food creates communion in all cultures and times. Thus, it is important to understand these rituals in the context of the total experience.”

So if the Zar dance ritual resembles elements of Tarantella, let us look at the Tarantella phenomenon itself, its relationship to city of Taranto, the tarantula spider, remnants of Greek civilization, and, in particular and in general, the culture surrounding festivals and assemblies.

TARANTO: Cultural Nexus of Magna Graecia

Stater from Taras or Tarantium, silver ca. 510 B.C., Naples, Santangelo Collection

The City of Taranto was established as a settlement by the Myceneans in 7th century B.C.E. Later in the 8th century it was re-named Taras by Greek colonists from Sparta. Legend says that the founder of the City Taras was saved by a dolphin which helped him ride safely to the Apulian shore, after a skirmish at sea, where he was thrown overboard and was about to drown.

Taranto is situated at the mouth of Mare Piccolo, one of the most extraordinary natural inlets of the Mediterranean for its size and safety, and it lies at the Ionian side of Apulia facing Africa. See maps in Appendix.

On the other side of peninsula, facing the Adriatic and on a clear day, more likely in winter, when the Tramontana wind blows from the Alps pushing the sea vapors toward Africa, one can see the mountain ranges on the Balkan side of the Adriatic. This kind of visual, navigational possibility made Apulia attractive to mainland Greece. Apart from some islands, including Sicily and the edges of the Mediterranean like the countryside near the Bosporus, this visual connection exists only from the Iberian Peninsula in the Andalus region near Gibraltar, where also on a specially clear day one can see across to Africa. Reading the Ulysses and Aeneas sea journeys and trials, one may glean what emotionally and cognitively these visual connections meant to the people of the ancient world. Later in this paper we touch upon a few more points from the maritime folklore to give examples of the seeming persistent practice of Tarantella-like dance forms.

Geographically there is a point that is approximately 50 miles (84 km) between today’s Albania and the Adriatic coast of Apulia. One can navigate back and forth to Greece without hitting Sicily and the mythical dangers of Scilla and Charybda. Although Calabria and Sicily were integral parts of Magna Graecia, Apulia and the safe haven of Taranto had a unique place in the mix.

This relatively easy navigable distance may account for Pliny’s attributing the origin of Apulia’s southernmost tribes of Messapians as descendents of nine youth and nine maidens of the Balkan Illyrians. The Mycenaeans founded early colonies in Apulia on both the Adriatic and Ionian shores. The earliest recognizable tribes of Apulia are known only as names, but some study of Apulian last names may reveal the now-dispersed descendants of Siculi, Ausoni, Chones, Morgeti.

Apulia occupies a geographically central position in the Mediterranean region. Rome always planned to dominate Magna Graecia, and from 170 B.C.E. its main line of conquest, Via Apia, was built from Rome to Brindisi. This town is equally distant from Rome, Athens and Palermo. Under the Romans, Brindisi took precedence over Tarentum, the Roman name for Taranto.

When the Romans entered the port of Tarentum in 282 B.C. the people did not fight against the fleet, because everybody was in the theater enjoying the hilaro – tragodia the fashionable form of comic theatre of the day.

The above paragraph and the following quote are adapted from “The History of the Greek and Roman Theater,” by Marguerite Bieber, (Princeton University Press, 1961, p. 137 and 164).

“…in the first century B.C. ……[the] art of acting reached its height in Rome. It followed upon the highest development of Roman dramatic poetry in the third and second centuries B.C., just as formerly in Athens and Greek Tarentum the peak of acting was reached in the fourth century following upon the culmination of classical tragedy and old comedy, which preceded it in the fifth century.”

We include these quotes in the brief description of Taranto to bring to the surface its cultural importance, deep connections to the development of theater on the Greek mainland, and in that way, connect both to Dyonisian and possibly Pan worship and celebrations.

Tarantula Spider: The Seed of the Dance

We have not found so far any discussion of reasons and origins for investing this particular species of spider as a cause of ailment. It seems to be understood by all writers through the centuries that there is a pestilence (Tarantismo), and here is the cure (Tarantella).

Lycosa tarentula is a spider found in great quantity around the town of Taranto and surrounding countryside, hence it name. The tarantula spider spends most of its life within its burrow, which is an 18-inch (45.5 cm) vertical hole with an inch-wide opening. When male tarantulas are between the ages of five to seven years, they leave the burrow in search of female mates, usually in the early fall. The males mate with as many females as they can, and then they die around mid-November. This happens at the time of harvest, when people are in the fields and often take siestas in the shade of a tree, rather then going back home, so as to return to harvesting in the afternoon’s cooler temperatures.

Tarantella Dances

The Tarantella dance traditions are totally woven into daily life, the cycle of seasons, work and rest, and celebrations in southern Italy. Three forms of Tarantella dances are known today. The first is Tarantella de Core, a courting dance for couples, often danced at weddings and public celebrations. The second is Tarantella Scherma, a martial or dueling dance for men, which is danced at country fairs, festas and animal markets, both as a show and as territory marking. Originally it was danced with rapier type weapons or knives, but today it is performed with the middle and index fingers projecting out of a fisted hand imitating a knife. The third is the form we are exploring in this paper, Tarantella Pizzica, the trance-healing dance most often performed by women.

Tarantella Pizzica

The Tarantella Pizzica is both an individual and a group healing dance, the origins of which go back to the ancient healing ritual of the Tarantati (those bitten by the tarantula spider), and their pilgrimage to Galatina (near Lecce). The last evidence of the event was seen on May 29, 1993 with the final dances of an old lady, who had been performing the danced ritual for the previous 26 years (cf. G. Di Lecce, La danza della piccola taranta [The Little Tarantula Dance], Rome 1994). This dance, observed and described since the Middle Ages, is composed of rhythms and melodies which can be slow as well as lively. Popular literature (15th to 20th C.E.) reports examples of a great number of dance forms performed by these tarantafi in which they also make use of several objects and accessories, such as swords, handkerchiefs, ribbons, mirrors, fans, shells, and other accoutrements.

Dances Resembling Tarantella Pizzica

In Egypt the comparable dances go by the name of Zar; in Algeria, they are called Jarjabous, and in Tunisia they are the Stimbali. In Morocco, they are performed by the tribe of the Gnavas, who claim Ethiopia as their country of origin. In southern Italy they are called Tarantella Pizzica.

The trance dance is a ceremony that aims to harmonize the environment and the participants. It is a form of passing of knowledge and healing a person, either on a spiritual or psychological level, of problems that may result from suppressed wishes or needs, or from some socially-induced repression. The trance dance is not a form of entertainment, nor it is an exorcism. Its sole aim is to heal the body and help the person. All people who partake in such a ceremony have the duty to support the afflicted person to the best of their abilities. In the Ethiopian liturgy, the clergy at times do trance dances and the drum is used.

The ritual dance can potently harmonize the layers of being and the person’s inherited psychological impulses, often starting from and focused on tangible as well as elusive individual problems. However, further questions emerge

Does the Tarantella Pizzica of southern Italy, like the Pan Worship and Dionysus Festivals of ancient Greece, carry the societal function of deepening inter-connectedness and group release, as well as personal healing?

What are the discernable dynamics of tuning the inner personal levels of an individual at the center of the ceremony, while at the same time nourishing the group’s well being?

Maritime Traditions and the Expansion of Hellenic Culture

To better understand the festival spirit, and possibly to glean something of the ancient Hellenic mind and its cultural context, we look briefly at some maritime traditions, folklore and the presence of sea in the daily life and ritual of the people of the Greater Mediterranean region. This may be helpful in understanding some aspects of ancient celebratory practices and the need for festivals and offerings. It also offers a loose framework for understanding Tarantella type of dance ceremonies.

In “ The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea,” edited by Peter Kemp (Oxford University Press, 1976), we find this statement:

“[Homer's] Odyssey records the adventures of Odysseus on his voyage home from Troy. Since Greece is a nation surrounded by the sea, it is not surprising that both these poems are interspersed with many memorable phrases describing the sea, such as ‘wine dark,’ and ‘with many voices,’ and ‘unharvested,’ etc. As a consequence they are considered to rank with some of the finest sea literature ever written.”

Odysseus and the Sirens; 5th century B.C. Attic vase

“Odysseus [Ulysses] is generally accepted as the font from which sprang the sailor-race whose voyages and adventures influenced and educated the Hellenic people. He was the archetype of the true Greek when their sea power was expanding across the Mediterranean from Black Sea to the Western Basin.”

Christina Pluhar in her introductory notes for the “La Tarantella – Antidotum Tarantulae,” Compact Disc, [pub. Alpha 503], writes:

“The origins of this ritual dance are attributed by some theorists to the cult of Dionysus that was disseminated in southern Italy over the centuries. Mythology has left us two tales of the origin of the tarantella that are still told in Sorrento and Capri Homeric poetry preserved in oral traditions. One of these relates that the Sirens tried to enchant Ulysses with their songs, but failed to do so because he had been warned beforehand and stopped his ears with wax. Thereupon the Sirens called the Graces to their aid, asking to be taught an erotic dance. But the Graces made fun of the Sirens and invented the tarantella, knowing full well that the Sirens had no legs and would not be able to dance it... Since that time the tarantella has been performed by the young maidens of Sorrento, who learned it from the Graces.–

Maritime Celebrations

One of the archaic festival forms was appeasing of the gods and celebration of successful enterprises, like landing safely, surviving a turbulent journey or simply finding one’s way. In this difficult task of survival, in some instances for navigation, mariners in ancient times used birds, particularly homing pigeons, crows and ravens. With the help of such birds, when land was sighted, approached and proper coordinates established, the crew would have a special Neptune ceremony, offering up a shipboard festival to give a sense of accomplishment and release, together with the need to give thanks and celebrate.

The fact that some elements of Neptune’s rites and shipboard festivals are practiced to this day is of interest to us, particularly that they culminate in intense rituals reminiscent of the descriptions of bacchanalian rites. The most practiced and famous, even controversial in same cases, is the ceremony of “Crossing the Line.”

The “Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea,” (Op. cit., pp. 213 and 214), says this in the “Crossing the Line” entry:

“ [These] ancient rites connected with the propitiation of the sea god Poseidon or Neptune. It was the custom to mark the successful rounding of prominent headlands by making a sacrifice to the appropriate deity, many of whom had temples erected in their honor on such points.”

With the spread of Christianity, many of the vows and oblations paid to ancient gods were transferred to honoring the saints. In 1529 the French instituted an order of knighthood called Les Chevaliers de la Mer in which novices were given the accolade when rounding certain capes.

Jal, in his Glossair Nautique, claims that in the middle of the 17th century it was the custom on French ships on crossing the equator for the second mate to impersonate Neptune and initiate all novices on board with a stout blow from a wooden sword followed by a dousing from a bucket of sea-water.

Today we can find the ceremony of Crossing the Line [Equator] still performed on a number of commercial, military and training ships. We return to “The Oxford Companion to Ships and the Sea”:

“Crossing the Line is a ceremony performed on board ships when members of passengers, crew are crossing the Equator for the first time during a voyage. Usually all members of a ship's company who have not previously crossed the line are initiated at a special ceremony held to mark the occasion. On the day the Equator is crossed one of the ship's company appears on the forecastle suitably attired as King Neptune, encrusted with barnacles, wearing a golden crown, a flowing beard, and clasping a trident. He is accompanied by his wife, Queen Amphitriate, an evil-looking barber, a surgeon of equally villainous appearance, some ierce looking guards, and as many "nymphs" and "bears" as the occasion may demand. After parading around the ship, court is held on a platform erected beside a large canvas bath filed with sea-water. After bestowing awards on distinguished veterans, King Neptune summons the novices one by one. After receiving the attentions of both surgeon and barber, the novices are tipped backwards into the bath, where the bears ensure that they receive a good dunking. This procedure earns them a certificate, which exempts them from a repetition of the treatment on any future Crossing of the Line that they may undertake.”

In the Neptune ceremonies the usual order and tightly defined roles are somewhat suspended. There is an allowance of the sense that the celebratory behavior of loosened censure has taken over, but fully knowing that it is contained by ship’s ground rules. For the reasons of maintaining balance and discipline, it is advisable for captains not to play the role of Neptune, thus traditionally it is played by the first mate.

Due to the unique position of ARTSHIP Foundation having been housed on an historic ship from 1999 to 2004, the author of this paper has carried on informal inquiries about Neptune-inspired “crossing the line” ceremonies aboard ships from among a number of their captains and sailors. Not everybody agrees, but some of the older captains, now in their 80’s, are adamant that after such ceremonies the ship's morale was tighter. Some sailors mentioned experiencing the feeling of being emptied, of being closer to every one and ready for work. By way of comparison, something akin to these feelings also may be experienced by a matron in the weeks after a trance dance ceremony, in which her family was supporting her, and the whole group may feel closer.

The image below is from a Crossing the Line ceremony held aboard the California Maritime Academy training vessel, TS Golden Bear, which became the ARTSHIP after it was de-commissioned from service.

Crossing the Line Ceremonies, 1950. Archives of the California Maritime Academy, Vallejo, California

Crossing the Line and De-Naming of Ships ceremonies, both dedicated to Neptune, remind us of the celebratory remnants of Greco-Roman civilizations.

Historic Comparison of Tarantella, Pan Worship and Therapeutic Dance

Having reviewed elements of parallel festival experience, let us look now at some historic texts on the Tarantella dance and compare them with contemporary writing on Pan worship and other therapeutic dances.

Antoine Furetière, in Dictionnaire Universel, 1690, says:

“Tarantula. Small venomous insect or spider found in the Kingdom of Naples, whose sting makes men very drowsy, & often unconscious, & can also be fatal to them. The tarantula is so called after Taranto, a town in Apulia where they are to be found in great numbers. Many people believe that the tarantula’s venom changes in quality from day to day, or from hour to hour, for it induces great diversity of passions in those who are stung: some sing, others laugh, others weep, others again cry out unceasingly; some sleep whilst others are unable to sleep; some vomit, or sweat, or tremble; others fall into continual terrors, or into frenzies, rages & furies. This poison provokes passions for different colours, so that some take pleasure in red, others in green, yet others in yellow. In some cases this illness can last for 40or 50 years. It has been said since time immemorial that music can cure the tarantula’s poison, since it awakens the spirits of the afflicted persons, which require agitation.

The fascination with the remedy for that disease, which was supposedly caused by a spider's bite and has been known since the Middle Ages as 'tarantismo,' remains even today inexplicably complex. And just as varied as the symptoms and causes of the illness are the musical forms that are meant to cure them.

We already have cited Christina Pluhar from her introductory notes for the compact disc “La Tarantella – Antidotum Tarantulae” where she writes that the origins of this ritual dance are attributed by some theorists to the cult of Dionysus, that was disseminated in southern Italy over the centuries.

Interestingly, as late as in the 1950's, the ethnomusicologist M. Schneider writes in his book La danza de la Spada y la Tarantella (The Dance of the Sword and the Tarantella, 1948):

“As for Tarantella, this is one of those animal‑like dances in which participants play different animals that are considered to be the reincarnation of the spirits of the dead. When these are unhappy they bring disease and death to man […]. This dance is meant to be a sort of rhythmic auto‑vaccine that is beneficial to the diseased. By adapting the rhythm to the disease or by identifying oneself with the “spirit” or the animal that caused it, the spirit is recognized, at which points it is made to fight itself by inverting all values. Once the physician, the dancer or singer gets hold of some of this destructive force, they can use it to fight this same negative force which elected to reside in the diseased person's body […]”

Image of music score for Tarantella, Apulia and two tarantulas from “Magnes, sive De Arte Magnetica” by Athanasius Kircher

Perhaps the most significant writing on the tarantella phenomenon is by Athanasius Kircher. In his treatise on healing, “Magnes, sive De Arte Magnetica” [Rome, 1641], Kircher collects and writes down the most repeated examples of tarantella tune and dedicates a section to the cure of the tarantula bite through music. He opens with a question:

“Why cannot those poisoned by Tarantulas be cured otherwise then by Music?”

In discussions and theories about Tarantella music and dance as a cure, Kircher touches upon important aspects of tarantella lore, its inner workings, facts, fiction and therapeutic dance tradition:

“The great power and efficacy that Music possesses for the arousal of changes in mood and affections…” Further on he states that: “ … by the agency of Music, the burdensome illness and affliction that stems from the poison of these Tarantulas may be driven from the afflicted, and the same restored to complete health.”

To engage us in his argument he brings an experience most people have had, that:

“… musical movement, penetrates the body, … … and stirs the vital spirits….

Following that logic Kircher traces the affliction:

“…fibers, membranes and articulations or musculi carry and harbor the hidden venom, and also hold within them the harsh moisture, the pungent and bilious humor…”

According to Kircher the poisons stirred by the right music would begin to heat up the organism. The inner organs and veins growing warmer will begin to pinch and stretch, as aresult of which the patient is driven to dance:

“Now the whole body is stirred by dancing and leaping, together with all the humors that it contains.”

He repeatedly argues that the continuous movement of dance will result in heat and increased warmth. And this heating up of the whole body leads to the stretching and opening out of the air holes, through which the poisons are exhaled and depart.

The following statement by Kirsher reveals his awareness of the complexities of Tarantella traditions and tentatively links them to number of musical healing traditions:

“The fact that such and such a musical instrument is pleasant and suitable in one case, and such‑and‑such in another, must be ascribed to the properties, nature and complexion, either of these spiders or of men. Hence it is necessary, when a person has been bitten or stung by one sort of Tarantula or another, to use the right sort of music or song for him.”

Karol Harding in her description of Egyptian Zar states:

“The Kodiais [the leader of the dance] expected to be a trained singer, who knows the songs and rhythms of each particular spirit. As she sings each spirit’s song and watches for reaction she is able to diagnosewhich type of spirit has taken possession and how to ‘treat’ it.”

If we replace the word spirit with spider, this description opens further questions for us:

Are they the Zar and the Tarantella inspired by the same or similar traditions?

Were they adopted and did they survive under different names and conditions throughout the Greater Mediterranean region which originated from the same tradition?

Hassan Jouad, an ethnomusicologist, in his “Les Aissawa de Fes – Trance Ritual,” (L’Institute du monde arabe, 1994), in notes for the compact disc (Harmonia Mundi) states:

“For the Aissawa, as for all brotherhoods of therapeutic trance, each human being is inhabited by a spirit, often the spirit of a predatory animal, whose desires and moods are independent from the desires and moods of the individual in whose body it takes shelter. The inhabited ‘meskun’ is dominated without knowing it. Subject to the whims of his inhabitant, he is made unbearable to others, unavailable towards God as well as his own self.”

The Hassan Jouad description of trance dance ritual, based on research and first hand experience, is a remarkable document. It articulates and brings us closer to the inner work and attitude of therapeutic dance participants. This articulation, however obliquely, helps a comparative study and research into the meaning of ancient practices and sheds some light on what might have happened in Dionysian “revels” and worship

The “archeology” of ancient dance is difficult and elusive. In material archeology it is easier to tell what is a barnacle and what is the terracotta of an amphora. In dance practices it is impossible to distinguish the original from additions.

Most scholars and practitioners of either Italian Tarantella Pizzica or Egyptian Zar agree that they are exclusive to women’s mysteries. People of Salento in Apulia, in the heel of Italy, claim that their Tarantella dances are more authentic than those of northern Apulia or the Neapolitan. Calabria has same remarkable Tarantellas of its own. Aissawa brotherhoods (all male), which practice similar notions of healing dances in North Africa, follow seemingly different pedigree from the 15th century. Some people in the west confuse this type of dance with an exorcism and attribute it to gypsies, due to a remarkable BBC documentary about gypsies in Egypt.

In spite of these seaming contradictions, and when it comes down to practice, some remarkable similarities emerge. A Hellenistic fragment describing ritual equipment for women is almost a list that can be and is used in many of the dance rituals today.

Hassan Jouad says:

“What the trance brotherhood proposes to its followers is that they recognize in their own behavior the signs which come from their inhabitants and accept them. By making himself accomplice to its enticement and by using his receptivity to rhythm, the inhabited may impose discipline on his ‘saken’ and make it show itself freely, but only during certain moments. Just as in a sort of pact, the follower accepts to let himself become dispossessed of his body and stripped of his ”me” during the span of a trance. He can thus give satisfaction to the inhabitant spirit in well-defined limits and in all security. Because this same rhythmic movement through which the follower lets himself be stripped of his human me and the responsibility which it bestows on him flow in a larger ‘me,’ comprised of the whole group of his fellow disciples, united by breath and voice, in the synchronized invocation of the divine presence.”

The word hadra means “presence” with, doubtless, this double sense of divine presence and presence of the inhabitant spirit.

It is interesting to compare the notes of ethnomusicologist Hassan Jouad with the writing of classical scholar Philippe Borgeaud who, in his “ The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece,” states:

“… Pan, Hermes’s son is rejected by his mortal mother, but no mischief or evil intention of his own brings on his abandonment; he is cast out because he frightens people, because he is disgusting. The infant Pan, a shaggy, bearded baby with horns, who laughs, is repellent. But we must go on to stress that he is repellent only to humans: the gods, and especially Dionysos, for their part find him charming. Pan is evidently the symbolic embodiment of the repressed. But everything man flees and rejects in order to distinguish himself from the animals makes him like to the gods. The myth seems to say: if we refuse the beast, we shall never never know how to resemble a god. A double and liminal figure, always transformed already, Pan meets man only to leave him at the precise spot where animality corresponds to the divine.”

Key Role of Leaders of Healing Dance Festivals

In researching Tarantella Pizzica of southern Italy, which led us to the healing dances and festivals in the Greater Mediterranean region, a very subtle, and almost (to non-practitioners) invisible role of the ceremony leader has emerged.

To help us understand this role we should remember for the moment that the captain of the ship does not take any mythological role at “Crossing the Line” ceremonies. This is very important. In this way he, like the leaders of some ceremonies and trance dances who may wear ceremonial costumes, keeps the festival proceedings safe and functioning for the participants

From descriptions of Zar, Aissawa practices, some 17th century accounts of Tarantella dances, as well as images on classical frescos and pottery, the role of a ceremony leader and counselor becomes more visible. This person carries responsibilities of creating physiologically safe space for the participants and helps them merge in to the “non me” realties of their belief as a form of respite, relief and healing. Also it is the leader’s responsibility to bring the person back to “this world,” and to recognize the right rhythm for the right person and ailment.

Karol Harding in her article “The Zar Revisited” for Crescent Moon magazine (July-Aug. 1996 p.9-10) says:

“The Zar is best described as a ‘healing cult’ which uses drumming and dancing in its ceremonies. It also functions as a sharing of knowledge and charitable society among the women of these very patriarchal cultures. Most leaders of Zar are women… ”

She continues (we re-quote for emphasis with some addition):

“Rituals are used to creating the setting. It has specific players and roles: a leader, a drum core, ‘patient’ and participants. It is community based, followers and members are not sent away to be cured…. It creates sense of community while it heals, embracing the individual within a community. The Zar is one of the rare musical traditions in which women play the leading role. The ritual is led by a woman called kudeyit, who usually professes a remarkably strong character.”

The description of the Zar leader with her knowledge, harmonizing abilities, understanding of repression and means of relief, paints a picture of a highly trained experienced person.

Ethnomusicologist Hassan Jouad (Op. Cit.) states:

“…it should be pointed out that the practice of the ecstatic dance is not reserved for the sole followers of the [Aissawa] brotherhood. It is open to all, to anyone who suffers. Here, people with few resources, the elderly, the physically handicapped find, with the help of others, the occasion to be completely receptive towards themselves in all legitimacy.”

The ad hoc or deeply established charitable institution provides for the ceremony’s expenses: stipends for musicians, incense and the altar needs, food, and of course for the ceremony’s leader. This oblique or clear-cut charity provides modes of living for the dedicated women who hold tradition and knowledge. This is an age-old practice, almost a common law institution, of a pastoral role for women. In talking to and observing some women, during our work in southern Italy in the 1970’s, we discovered a set of local values, sometimes unspoken vows of “poverty” and service — as if to insure that the practices of dance ceremonies will be selfless and directed to the well being of the community and to the person who is in a process of healing. Like the modern psychotherapist or artist, the leaders of trance dance come in varying degrees of ability, selflessness and non-commercialism. As in any profession there are charlatans, exhibitionists, well meaning, half-baked and superbly attuned practitioners. If we look back at the fresco from Museo Nacionale in Naples with the sleeping bacchanite, the attentiveness and the seriousness of the person watching over the prostrated and vulnerable women, we are inspired by deep respect.

This is an important element of our findings: what appears to the casual observer as chaotic and wild music and dancing has an inner traditional structure and meaning. It expresses itself through phased build up, it is subtly cared for by the festival leader, and this may be apparent only to the skillful and sensitive ethnomusicologist. Here we attempt to bring an informed sense of the ephemeral elements of healing dances for consideration.

Music: Historic Resonance

In researching the possible sounds of and musical influences on Tarantella dances and associated traditions, we came upon the manuscript known as ‘Lo’ now in the British Museum Library. In it are contained a number of dances known by their catalog number: additional 29987, and called “Istapittas.”

The Medici family owned this manuscript in the years roughly preceding and coinciding with the events of 1438, when the Byzantine Emperor John Paleologus came to the west in the last endeavor to enlist its help against the Turks. He came with a train of scholars, artists and churchmen. No western aid was forthcoming, and the Emperor returned empty-handed to Constantinople to face inevitable tragedy alone. Behind the scenes an understanding was reached. Fourteen years later Constantinople fell, but all that was important had already been transferred to Florence.

Some scholars of the Renaissance argue that the idea of the famous Platonic Academy was suggested to Cosimo Medici by the Greek scholar Plethon. He was an important member of the Emperor’s circle who seemed later to have lived in Florence.

We know that Aristotle’s work and some other Greek material was preserved by Arab scholars, translated and brought to Florence, together with collections of Greek and Roman artifacts and sculptures, inspiring a whole new school of learning, art and artists.

A thesis titled “The Middle Eastern Influence on Late Medieval Italian Dances — Origins of the 29987 Istapittas,” by Michele Temple, explores unique features of this rare collection of actual sounds from history. In her introduction she writes:

“Both the text, which shows Tuscan linguistic traits, and the music are written in a manner indicating dictation rather then copying.”

The music is naturally the inseparable partner of dance. To reconstruct the Greek music beyond well-known existing fragments, in particular the music of festivals and Pan worship, is an impossible task. But coming into contact with and listening to a number of recorded versions of Istapittas, two tantalizing questions arise:

Are the Instapittas, perhaps, a rear glimpse into ancient festival dance music preserved by Arab and Byzantine practitioners, like the works of the philosophers?

Was this the reason for them to be collected by the powerful Medici family?

Significance of “Just Excess” and “Recovered Closeness”

In his writing on “The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece,” Philippe Borgeaud explores the inner workings of festivals and assemblies and offers in-depth insights that are worth noting as a conclusion of this paper:

“Pan’s dance (in a word) conjoins two terms of a transformation: before and after.The ‘perfectly initiated dancer’ makes others dancers dance with them; his music calls forth harmony, that humane order in the dance of which Plato speaks. But he himself remains at the animal level; he leaps.

In another passage, Borgeaud writes:

“The krotos (sound of clapping), gelos (laughter), and euphrosune (good humor) thus appear as constitutive elements of panic ritual, and this not only in the sense that festive gestures were an ordinary part of most Greek sacrifices. The same point can be made about the dance, which played a fundamental part in the cult of Pan.

The god made his presence felt in the excited and turbulent chorus of his votaries. A certain balance is achieved by the festival, which brings together in ritual the two extremes of Pan potency, panic and possession, but in such a way that each shows only its positive aspect: the god is present without alienation and the distance between god and worshipper is kept to a minimum. By panic, Pan atomizes a social group (an army), fragments it, destroys its solidarity; by possession, he evicts the individual from his own identity. In his dance and festival, the individual, while remaining himself, loses himself. This is perhaps what the Pharsalian inscription cited earlier means by “just excess.” The chorus simultaneously displays social solidarity with the extrasocial: it communicates with nature and the gods. The Epidaurus hymn remands us that Pan’s music and dance restore a threatened cohesion. Dance, laughter, and noise become, in th festival, signs of a recovered closeness.

From the material presented here, we can glean that elements and attitudes of Dionysus and Pan worship of ancient Greece can be found in the practices of southern Italian Tarantella. We also can observe that in other territories of Greek influence similar dances exist under different names, and that most of the trance dance ceremonies throughout the centuries were danced and led by women for women, with some exceptions.

End Piece: Some Open Questions Emerge

What are the deep meaningful responses triggered by rhythm and dance in the participants?

Are they the symbolic, ritualized interplay of affliction and recovery that help reintegration of the afflicted person into the community?

And what is in that process that unifies the entire assembly?

What are the deep continuing human traits that draw people to festival practice and healing dances of Tarantella type?

Are the stylized realties of shared myth and stories a binding agent?

What role do festivals play in how we, in the archaic recesses of our being, ward off unbearable levels of irrational anxiety?

Are the festivals, together with entertainment, cultural opportunities and possibilities of “people watching” part of urban closeness and an expression of implied reassurance?

Two Terracotta Statuettes of Dancers, height 15,5 cm, mid 3rd century B.C.E., Museo Archeologico Regionale, Siracusa, Sicilia

Appendix

Bibliography

Allen, E. 1969, Stone Shelters, MIT Press, Cambridge.

Bieber, M. 1961, The History of the Greek and Roman Theater, Princeton University Press.

Borgeaud, P. 1988, The Cult of Pan in Ancient Greece, University of Chicago Press.

Di Lecce, G., The Legend of the Italian Tarantella: Taranta, Pizzica, Scherma (compact disc), introductory notes, Arc Music, Italy.

Furetiere A. 1690, in Dictionnaire Universel.

Godwin, J. 1979, Athanasius Kircher: A Renaissance Man and the Quest for Lost Knowledge, Thames and Hudson, London.

Greco, E. 1996, “City and Countryside” in The Greek World: Art and Civilization in Magna Graecia and Sicily, G. Pugliese Carratelli (ed.), Rizzoli, New York.

Harding, K., “The Zar Revisited”, Crescent Moon (July-Aug. 1996), 9-10.

Homer, Od. XI. 581.

Hooreman, P. 1960, Dancers Through the Ages, Uffici Press, Milan.

Jouad, H. 1994, Les Aissawa de Fes: Trance Ritual (compact disc), notes, L’Institute du Monde Arabe, Morocco.

Kemp, P. (ed.) 1976, The Oxford Companion to Ships and Sea, Oxford University Press.

Kirsher, A. 1641,Magnes sive de Arte Magnetica (Opus Tripartium), Rome.

Kraemer, R.S. (ed.) 2004, “Ritual Equipment for a Women’s Festival in Hellenistic Egypt” in Women’s Religions in the Greco-Roman World: A Sourcebook, Oxford University Press.

Maiuri, B. 1957, Museo Nazionale Di Napoli, Instituto Geografico De Agostini, Novara.

Mertens, D. & E. Greco 1996, “Urban Planning in Magna Graecia” in The Greek World: Art and Civilization in Magna Graecia and Sicily, G. Pugliese Carratelli (ed.), Rizzoli, New York.

Mueller, F.L., Istorija Psihologije, Zorana Stojanovica, Novi Sad 2005, translation of Histoire de la psychologie de l'antiquite a nos jours, Paris 1960.

Oesterly, W.O.E. 2002, Sacred Dances in the Ancient World, Courier Dover Publications.

Pluhar, C. 2001, La Tarantella: Antidotum Tarantulae (compact disc), introductory notes, Alpha Productions, Paris.

Sappho 1999, “Dancers” in Poems, W. Barnstone (trans.), Green Integer, Los Angeles.

Schneider, M. 1948, La danza de la Spada y la Tarantella [The Dance of the Sword and the Tarantella].

Seyffet, O. 1956, Dictionary of Classical Antiquities, H. Nettleship & J.E. Sandys (eds), World Publishing Company.

Temple, E. 2001, The Middle Eastern Influence on Late Medieval Italian Dances: Origins of the 29987 Istampittas, Edwin Mellen Press, New York.

Turcan, R. 2006, Cults of the Roman Empire, Blackwell Publishers.

Photograph from ARTSHIP Ensemble rehearsals of their production of “Tarantella, Tarantula”, Fall 2006